It penetrated, in the form of previously unknown, stylised Russian patterns, into painting, theatre, stage design, music and book industry and reformed them forever. It opened a new Russia for Europe and it was such a sensation in the West that till our days the works by great Mir Iskusstva artists – Alexandre Benois, Léon Bakst, Viktor Vasnetsov, Konstantin Korovin, Alexandre Jacovleff, Valentin Serov, Boris Kustodiev, Nicholas Roerich, Eugene Lanceray, Isaac Levitan, Yelena Polenova, Natalia Goncharova, and Konstantin Somov, among others, – are in huge demand with collectors worldwide. They remain top lots at the most famous auction houses and are a preferred and profitable investment. The list of people who were in the Mir Iskusstva movement is significant and impressive. The achievements of these talented artists were unprecedented and indisputable. Each being a rear talent, they got together to promote new ideas and concepts and achieved unbelievable heights. They managed to change and enrich the history of classical art and open to the world the unknown and multi-faceted Russian art by means of outstanding projects, exhibitions and performances. They developed and shaped new genres and techniques: from costume and revolutionary set designs to a new form of a literature and artistic project. The world art continues to build on their findings. Mir Iskusstva artists remain extremely relevant today: they shaped, to a significant extent, our contemporary visual images, from the St. Petersburg period in Russian history to the ideas of how a deluxe magazine, a gift edition, sceneries and costumes, or interiors should look like. In the beginning Mir Iskusstva, which later grew into a great and important movement, was a circle of young and ambitious artists, with lively hearts and minds, who studied together in gymnasiums, the university and, later, the Academy of Arts. These were Alexandre Benois, Dmitry Filosofov, Léon Bakst, Konstantin Somov, Sergei Diaghilev, Konstantin Korovin, and Walter Nouvel. Alexandre Benois was the initiator and ideologist of the movement. A passionate lover of theatre, he never missed a performance when he was a gymnasium and then university student. Benois was fond of works by Pyotr Tchaikovsky, who was not praised much by critics at the time, and he began to involve the members of his circle in studying this music. Two works by the composer shaped the visual benchmarks of the young artists. The first was The Sleeping Beauty. After the ballet was staged for the first time in 1890, Benois’ friends Diaghilev, Filosofov, Bakst, Nouvel, Somov and Korovin formulated the ideas of the reforms they wanted to pursue in Russian art, which later became the fundamentals of Mir Iskusstva. They were impressed with the historical realities reproduced in The Sleeping Beauty, which showed the childhood of the future Louis XIV and told the fairy tales by Charles Perrault. The future Mir Iskusstva artists were fascinated by the mythological life, filled with classical and Renaissance aesthetics in Russia. Alexandre Benois wrote in his Memoirs: “This admiration for The Sleeping Beauty directed my interest […] back to the ballet. It infected my friends, and we gradually became real ballet fans. So was created the main prerequisite for our joint activities several years later in a sphere which brought us worldwide success. ”Tchaikovsky’s The Queen of Spades, with its images of St. Petersburg, was another strong impression for the artists. They began to study the European architecture of the city and its suburbs – Peterhof, Oranienbaum, and Tsarskoye Selo. They studied painting and visited theatres, concerts and exhibitions. With their growing love for Romanticism, Peter the Great’s Baroque, and the Renaissance, these enthusiasts decided to reshape Russian art. They wanted to discard the outdated artistic traditions of the Peredvizhniki with their focus on reality and common people. They strove to return to Russian art its main quality – the artistic nature – and fill it with aesthetics, beauty and fineness. The movement did not aim to create a separate current in the art. Benois stated that, “Our circle did not have a direction. We had taste instead.” Later Mir Iskusstva artists used their best endeavours to present this new Russian art to the West. Their position remained the same in any artistic project they undertook later: art for the sake of art. Because of their special interest to foreign art, many of them were tagged as “westerners” in literature and artistic circles.

Window to Paris

In addition to Alexandre Benois, the most prominent ideologist and promoter of Mir Iskusstva was Sergei Diaghilev, who later became a famous patron and impresario. Diaghilev played a leading part in resolving all organisational and practical tasks. His idea was to bring together young artists of St. Petersburg and Moscow. Sergei Diaghilev demonstrated unprecedented qualities of a producer – energy, initiative and persistence – when he organised the first international exhibition. He persuaded, motivated and speeded up its participants. The main thing was, however, that he managed to raise funds and promote Mir Iskusstva projects. In 1898 Diaghilev organised a joint display for artists of the two capitals at the Exhibition of Russian and Finnish Artists. The participants included Léon Bakst, Alexandre Benois, Viktor Vasnetsov, Konstantin Korovin, Mikhail Nesterov, Eugene Lanceray, Isaac Levitan, Sergey Malyutin, Yelena Polenova, Andrei Ryabushkin, Valentin Serov, and Konstantin Somov, among others. Everything was arranged with big taste. The design of the exhibition space was unseen for St. Petersburg and Moscow: the hall was decorated with flowers and an orchestra was invited to play on the opening day. Diaghilev even managed to invite members of the Tsar family, including the Emperor himself, to the opening. Finally, he arranged the display of works, which were already a success in Munich. The exhibition pushed Diaghilev to fulfil his dream – set up an artistic society and a unique magazine about arts. Also in 1898, he persuaded Savva Mamontov and Princess Maria Tenisheva, prominent philanthropists and lovers of art, to finance his monthly magazine. Soon the first issue of Mir Iskusstva appeared in St. Petersburg. The design and contents of this new Russian periodical, from its cover to illustrations and fonts, were revolutionary. It was a work of art. In particular, authentic font models of the times of Empress Elizabeth were found, which were used to produce font plates for the magazine in Germany. The magazine was printed by Golike and Wilborg’s publishing house. The success of the magazine became possible thanks to its editorial board and managers – Sergei Diaghilev and Alexandre Benois. They worked right at Diaghilev’s apartment, where they drew, edited texts, retouched photographs (Léon Bakst’s hobby), wrote and solved accounting matters. Artists put all their time and effort to make the magazine. Valentin Serov, who joined the movement, did not participate much in this work but he enjoyed staying at the office and making caricatures. He produced sharp and sometimes rather harsh pictures of his friends, including Diaghilev, Benois, Nouvel, Grabar and Bakst, which were later collected by Benois. Mir Iskusstva was Russia’s first artistic movement which had its own publication. The magazine cooperated with writers, philosophers, poets and best artists. It published regular updates on foreign arts, reviews of foreign publications and exhibitions, and reproductions of contemporary paintings and graphic works. Its objectives were to gradually get closer to international modernism and popularise Russian art of the 19th and early 20th century. At the same time, Mir Iskusstva remained a space of creative freedom, without a definite tendency or trend. The magazine was published until 1904. But what happened with the movement? Headed by Diaghilev and Benois, its artistic core were Konstantin Somov, Léon Bakst, Eugene Lanceray, Mstislav Dobuzhinsky and Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva. Alexander Golovin, Ivan Bilibin and Nicholas Roerich were also part of the movement. Valentin Serov joined the movement as an authoritative master of the “older generation.” Igor Grabar, a critic and researcher, was closely connected with its leaders. The exhibitions of 1899-1903 also displayed works by Mikhail Vrubel, Alexandre Jacovleff, Konstantin Korovin, Isaac Levitan, Mikhail Nesterov, Viktor Vasnetsov, Sergey Malyutin, and Paolo Troubetzkoy, among many others. Promoted by the magazine, Mir Iskusstva artists began to exhibit their works. Their first five exhibitions (from 1899 to 1903) were an enormous success. The paintings on display included works by sixty artists, including prominent European masters such as Claude Monet, Gustave Moreau, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, and James Abbott McNeill Whistler. In 1902 Mir Iskusstva artists exhibited their works at the Russian section of the Exposition Universelle in Paris, where Konstantin Korovin, Filipp Malyavin, Valentin Serov and Paolo Troubetzkoy received the highest awards. Then the Russian art exhibitions took place in Salon d’Automne in Paris and later in Berlin and Venice.

Mir Iskusstva on European Stages

Sergei Diaghilev, being a skilful impresario, a businessman and a lover of music, ballet and theatre, now began to bring to Europe Les Saisons Russes, which raised a furore. From that time on, the Old World could not imagine its cultural life without Diaghilev’s annual seasons. Innovative opera and ballet performances, staged by young directors and choreographers based on classical and modern music, gathered leading singers and dancers and showcased revolutionary costume and set designs by Léon Bakst, Alexandre Benois, Ivan Bilibin, Alexander Golovin, Konstantin Korovin, and Nicholas Roerich. Thanks to them, the Russian theatre got rid of sceneries, which were simply a supplement to the plot. Everything presented to the European public was magnificent and splendid: each detail of a performance, costume or sound was a masterpiece. Paris waited for and welcomed Diaghilev’s seasons for five years in a row, from 1909 to 1914. Les Saisons Russes were what brought fame to Mir Iskusstva and opened a new world for the West – the new Russian culture and its high and grand art. Another reason for Europe giving a standing ovation to Diaghilev’s seasons was that they reformed the theatre. Innovators Alexandre Benois and Léon Bakst guided this process. Beyond music, everything was different: costumes, sceneries and stage direction. Benois wrote in his memoirs, “I am absolutely convinced that our Russian season can become the start of a new era of the French and Western theatrical art.” Mir Iskusstva artists were the first who began to produce costume designs, showing an actor in a movement in order to determine his or her character, image and even a direction for the choreographer. Here Léon Bakst was obviously the most influential figure and from that time on he remained the only and unrivalled in his mastery. Bakst’s talent for decorative design manifested itself in the most vivid fashion during Les Saisons Russes. The achievements of the modern set and costume design, as well as the success of Diaghilev’s performances, were his merits. Bakst created an unmatched costume design, “a feast for the eyes” in exquisite and fantastic shows. Gorgeous and lapidary ornaments, bright colours and rich decorations, fabrics, accessories and details were extremely impressive. Most of Bakst’s costume designs were festive and bright in colours and were often richly decorated with gold – the brilliance and luxury of eastern patterns represented with the artistic approach of the Renaissance. The artist’s fantasy and his surprising discoveries in terms of colour combinations delighted. Bakst designed ornaments just for pleasure and then sophisticated them as a jewellery maker. This is the reason why his costume designs are still regarded as rare and precious works of art. They are present in the best world museums and private collections and are quickly sold by leading auction houses.

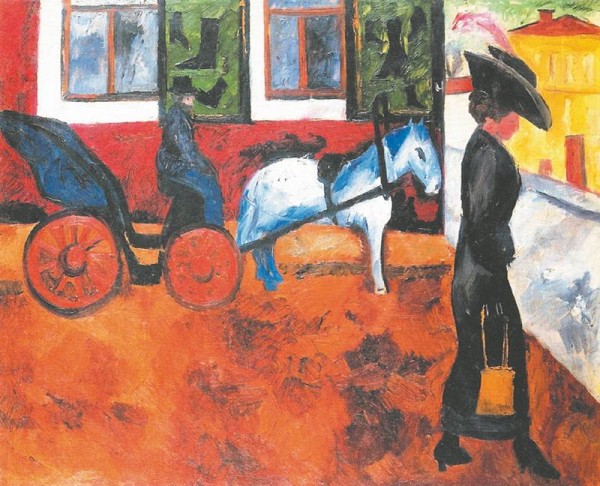

Exquisite Painting

In contract to the Peredvizhniki’s works, with their harsh realism and stories about common people, paintings and graphic works by Mir Iskusstva artists were impressively fantastic, elegant and delicate, paying homage to the past centuries. They reproduced a “dollish” style of the Rococo and the noble rigour of the Russian Empire style, a deliberately wonderful and non-existent reality of court scenes and splendid costumes. Mir Iskusstva artists created a special, lyric type of historical landscapes, which were painted with elegy (Alexandre Benois) or cheerful romanticism (Eugene Lanceray). Their works impress with sophisticated decorativeness, and thin, ornamental lines in graphics (Léon Bakst, Natalia Goncharova), as well as non-coincidental, masterful colour combinations, transparency and aerial mixtures of matte shades in paintings. All of them are an abundance of beauty, as it is subjectively understood by each artist. Book design also flourished at the time thanks to Mir Iskusstva artists. They worked proactively on the first (and largest ever) edition of textbooks on Russian history. Several years before WWI, Joseph Knebel’s publishing house in Moscow issued a set of fifty big chromolithographs, the originals for which were made by Mir Iskusstva artists. This was the first time when students at schools got an illustrated presentation of the history of the state. The artists created a series of talented and memorable images of the St. Petersburg period in Russian history – visual presentations of historic events, which the nation could be proud of. Several years ago, Alexandre Benois’ work At the German Quarter (Peter the Great’s Departure from Lefort’s House), created for this series of Russian History Pictures and reproduced on postcards and big prints, was sold in Moscow for 16.275 million roubles ($555,000). In its initial form, the Mir Iskusstva movement existed for only five years, from 1898 to 1903. However, it had a cardinal influence on the development of Russian art and gave a powerful impetus for its followers, as an expression of the freedom of thoughts and opinions in art. The second phase of the movement began in 1910. Benois could not stop and continued to bring together gifted and extraordinary artists. Yet, this stage was different. The destinies of Mir Iskusstva artists, who were dispersed by the Russian revolutionary catastrophe of the 20 century all over the world, were tragic for the most part. Because of forced and massive emigration after the Revolution of 1917, the lion’s share of their works was created abroad, outside Russia. Most of their paintings, opera and ballet costume and set designs, unique illustrations, and literary works, which were created in the times of hardships and nostalgia, were preserved till our days and now form part of the best museum and private collections. They are now beyond time.

Mir Iskusstva Today

The works by Mir Iskusstva artists are recognised masterpieces in the world culture. At different times, the movement was represented by the most prominent Russian artists: Alexandre Benois, Léon Bakst, Mikhail Vrubel, Alexander Golovin, Mstislav Dobuzhinsky, Konstantin Korovin, Boris Kustodiev, Eugene Lanceray, Nicholas Roerich, Mikhail Nesterov, Valentin Serov, Konstantin Somov, Alexandre Jacovleff, Viktor Vasnetsov, Natalia Goncharova, Ivan Bilibin, and many others. They played an important part in the history of art and left a significant legacy, which remains an indisputable artistic treasure. The largest museums of the world exhibit Mir Iskusstva artists or their separate works. The circle of investors who prefer this period in Russian art and buy artworks through art dealers at auctions is growing. Mir Iskusstva artists have the highest ratings at the leading auction houses such as Sotheby’s, Christie’s, Bonhams, and MacDougall’s. Their sketches, illustrations, costume designs and paintings ensure a quality return on investment. In the second half of the 2000s, Alexandre Benois, Léon Bakst, Konstantin Korovin, Boris Kustodiev, Alexandre Jacovleff, and Natalia Goncharova remained collector’s preferred investment targets among Mir Iskusstva artists.

Some facts:

• The unique collection of watercolours and set and costume designs by Alexandre Benois, sold at Sotheby’s in late November 2011 at a record high price, was the largest ever offered for sale at an auction. Before the auction, some works were displayed at French and Italian museums. This private collection was previously owned by the artist’s family. The items sold included portraits of Benois’ family members, watercolours, landscapes, book illustrations and sketches for set designs. The lots of special interest for collectors and art lovers were scenery sketches and costume designs for Igor Stravinsky’s famous Petrushka ballet and The Nightingale opera staged in Paris in the early 1900s by Diaghilev’s Les Saisons Russes. Benois’ sketch for The Nightingale was bought by an anonymous purchaser for $235,500 (with an initial estimate of $50,000). The collection was sold for a total of $3.1 million, two times above the estimate. This latest auction by Sotheby’s set a new record price for Alexandre Benois’ works.

• In 2011 the most expensive graphic work at MacDougall’s was Léon Bakst’s set design Le Port de Famagouste for La Pisanelle ou la Mort Parfumee (staged around 1913). Its price (£850,000) was twenty times above its initial estimate of £40,000-60,000. In May 2012 a watercolour by Léon Bakst (The Yellow Sultana) set a new price record at Christie’s, where it was sold to an anonymous buyer for almost $1.5 million, while its initial estimate was $560,000-700,000 (almost three times above the estimate). In November 2013, Bakst’s Bathers on the Lido, Venice was sold at MacDougall’s for £500,000 ($815,000).

References:

• Fenomen (Phenomenon) Literature and Art Almanac, No. 1(5), January-March, 2008.

• Alexandre Benois. Memoirs

• Boris Nosik. From Nevsky to Montparnasse: Russian Mir Iskusstva Artists Abroad.

• Chugunov, G. Valentin Serov in St. Petersburg. Biographies and Memoirs.

• Popular Encyclopaedia of World Art.

• History of World Costume (http://www.costumehistory.ru)

• Auction reviews by artprice.com, artinvestment.ru, RIA Novosti, Luxlux.net